We return to the “Palliser” series now and consider the two novels which form the core of the politics in that group of novels: Phineas Finn and Phineas Redux. The first of these in the Trollope Society edition includes 20 illustrations by Millais from the first edition – it was published in serial form in St Paul’s Magazine in 1867-69 and in book form immediately thereafter by Virtue and Co. The Trollope Society edition of the second novel includes 24 illustrations by Francis Montague Holl taken from the 1874 Routledge edition rather than the first edition. The Folio Society editions of both novels each include 20 illustrations by Llewellyn Thomas. We therefore have the opportunity not only to compare and contrast Victorian and modern takes on the novels’ scenes and characters but also two different illustrators from the time the novels were originally published.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing and it is evident when considering the subjects chosen by Millais in Phineas Finn, working contemporaneously with the publication of the novels, and Llewellyn Thomas, working some 120 years later with the benefit of knowledge of events described at the opening of the second novel. Millais featured Mary Flood Jones in five of his twenty illustrations, including depictions of her with Phineas which top and tail the book as the first and final illustrations; Thomas does not include a single illustration of the woman whom Phineas marries at the end of the novel on his return to Ireland. Thomas’s decision to relegate Mary to the role of minor secondary character no doubt reflects the knowledge, not available to Millais when illustrating the book, that she will die as a result of pregnancy complications between the end of that novel and the start of the sequel, thereby enabling the eponymous hero to return to the fray in Westminster.

Indeed, the relative importance of the four principal love interests which distract Phineas from the serious business of pqolitics throughout the novel by counting the number of illustrations in which they appear.

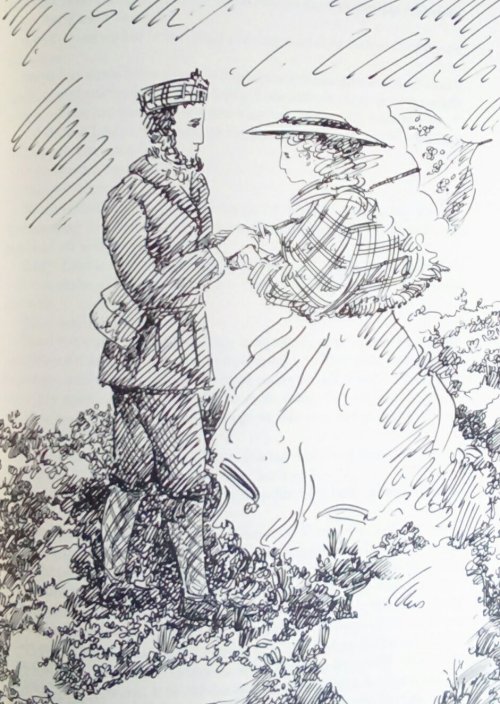

The clear winner in this respect for both Millais and Thomas is Lady Laura Standish, who enters into a loveless marriage with Mr Kennedy, in spite of being infatuated with Phineas, for what must be ascribed as purely political motives. Millais depicts Lady Laura eight times, four of which (including two alone with Phineas) are before her marriage. Thomas depicts Lady Laura five times (i.e. in nearly one third of all his illustrations) including one with Phineas which is also the subject of one of Millais’s illustrations – the moment when Phineas while walking with her at Mr Kennedy’s highland estate attempts to propose to her only to discover that she has just engaged herself to Mr Kennedy. Thomas lays out the scene almost identically to the Millais illustration with Phineas, in highland garb, to the left and Lady Laura to the right, facing him.

Millais also depicts Phineas’s second love interest, Violet Effingham, four times – only half the number of appearances of Lady Laura, and all of these occur in the earlier parts of the book, before she marries Lord Chiltern. Thomas, similarly regards her as of lesser interest, featuring her in only one illustration.

Millais pays least attention to Madame Max Goesler of all Phineas’s admirers. She is only depicted twice and in both she is not with Phineas but with the old Duke of Omnium, who is infatuated with her. I have to confess to finding Millais’s depiction of her less than alluring when engaged in intimate conversation with the Duke, stopping always just short of indiscreet behaviour because she has a certain, strict moral code, which allows her to flirt with the old man but take it no further, whatever society may be thinking she is doing. It is interesting to compare this with the, to my eyes, more sensual depiction of Phineas and Lady Laura deep in conversation and similarly engrossed in each others’ company.

Thomas does not depict this scene but shows the ill-matched pair out of doors with Madame Max facing away from the viewer with the scene which she is observing alongside the Duke taking up the bulk of the illustration. He also follows this approach in the first of the two illustrations of Madame Max with Phineas – they are sidelined and face away into the main scene depicted – before finally depicting her “facing the camera” in the last illustration of the novel – thereby benefiting from 120 year’s hindsight to contrast his own final image for Phineas Finn, showing him with the woman who will become his second wife at the end of the next novel, with Millais’s depiction of Finn with his first wife whom he marries at the conclusion of the first book.

It is interesting to note that the overwhelming majority of Millais’s illustrations are portrait, rather than landscape, making them more readily suited to book format than for the column layout adopted by many magazines published at the time. Millais also invariably depicts the characters full length thereby maintaining a slightly distancing, observer role for the reader when looking at the pictures. Llewellyn Thomas has followed this convention creating a more measured impression that is softened somewhat by his looser, free-flowing style of drawing, which depends for its effect more on the creation of an overall impression than reliance on details as some of the modern illustrators commissioned by the Folio Society, such as Alexy Pendle who drew the illustrations for the Barchester novels, have done. This gives the Palliser series in the Folio edition a consistency of style but at the expense of variety or light and shade in the depictions of the characters.

We can now turn to Phineas Redux which in the Trollope Society edition is illustrated by Francis Montague Holl who was engaged in 1869 by William Luson Thomas to work on his new illustrated newspaper The Graphic. Holl’s 24 illustrations for the novel were reproduced in the Routledge edition, published in 1874, from the original plate engravings. Holl was noted for his sombre style in paintings such as No Tidings From The Sea, depicting the family of a fisherman waiting for news after his boat has failed to return, and The Village Funeral.

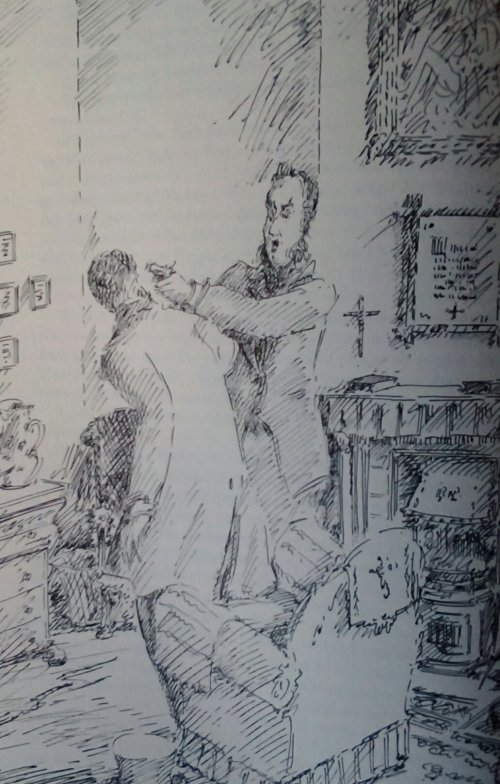

This darker style is carried through into the engravings Holl used to illustrate Phineas Redux. His technique creates a dark background with pictures emerging from the shadows which contrasts markedly with light backgrounds which typify Millais’s illustrations – and, for that matter, those of Llewellyn Thomas. This is put to good effect in the dramatic scene in which Phineas is confronted by Mr Kennedy when he visits him at his rooms. The ill-lit interior may be an accurate reflection of a typical, poorly lit Victorian room, but it also gives a figurative insight into the despair and madness of Kennedy.

In contrast, Thomas’s image of the same scene – one of only three which are depicted in both editions, conveys the sense of Kennedy’s incoherence through the wild expression on his face, the melodramatic posture of the man and implicitly through the loose freehand cross-hatching used to create the light and shade in the image.

The second duplicated image is the depiction of another pivotal scene in which Madame Max is with the elderly Duke of Omnium when he attempts to propose to her and she carefully sidesteps the offer of marriage without giving offence to the old man. This is one of six appearance she makes in Holl’s illustrations and four in Thomas’s, both artists rightly reflecting her increased importance in this second novel with more frequent depictions. However, Holl chooses to depict her alone twice as she struggles to master her feelings for Phineas, which she believes are unrequited, and does not picture her with Phineas until they are finally brought together after she has successfully brought about his release from prison. Here he creates a tranquil expression on her face which is more appealing, to my mind, than Millais achieved when depicting her at her supposedly most alluring when behaving coquettishly with the old Duke in the earlier novel.

Holl, with his 24 illustrations, has scope for greater variety in subject matter than Thomas with his sixteen. Holl uses this to explore the subplot of Adelaide Palliser’s romance with Gerard Maule and to twice depict Lizzie Eustace, who is a relatively minor character in the novel, albeit one who would be very familiar to readers as the principal anti-heroine of The Eustace Diamonds, the intervening novel between the two books featuring Phineas Finn in the middle of the “Palliser” series.

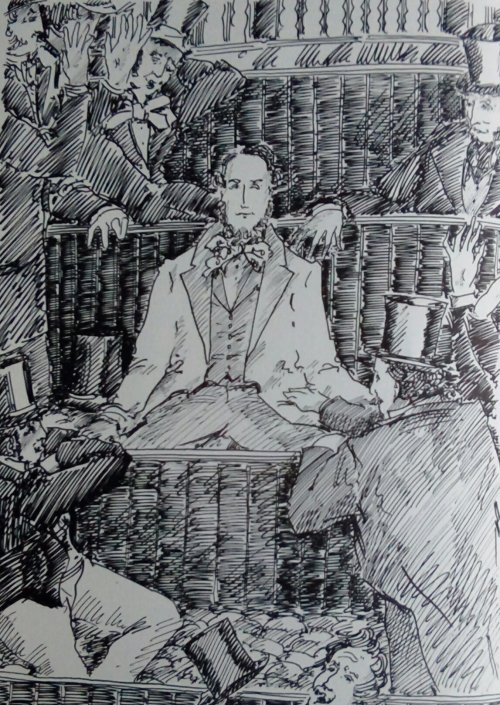

Holl was also able to balance the framing of his illustrations using nine landscape views and fifteen portraits to give broader perspectives where he wished. Presumably this was made possible through publication across two newspaper columns. This is put to good effect when depicting Phineas in his cell during the trial. Here the atmosphere of gloom, both literally in the room itself and metaphorically in Phineas’s despair, is conveyed through the dark shadows in which Lady Laura, his visitor, is almost obscured, much as Phineas was in the first illustration of the novel when he visits Lady Chiltern.

At the outset of the novel, Phineas has been depicted by Holl as an older, more careworn man than Millais portrayed. Gone is the luxuriant beard, upright carriage and clear brow to be replaced by a thinner, almost drawn face, a middle-aged stoop and a frown. Evidently Holl is depicting a man who is still grieving for his lost wife and child. Indeed, in early pictures Phineas is invariably seen in shadow or even facing the wall with his face hidden from the reader to emphasise his psychological state. Now, we find him bearded but dishevelled in prison, reflecting further developments in his character which are less clearly defined in Thomas’s depictions of Phineas, whose countenance, including his featured beard, show comparatively little change through the different passages of the book in the Folio edition.

Both the Trollope Society and the Folio Society editions end with illustrations of the final, tragic meeting between Lady Laura and Phineas. The contrast in approach is marked. Thomas, with his lighter, airy style, does not convey to me the sense of finality in the embrace of the two former lovers. I am not sure that Lady Laura’s upturned face and Phineas’s benign look express the moment appropriately and may be mistaken for a pleasant tryst in an ongoing courtship.Holl, on the other hand, shows Lady Laura clinging to Phineas, her face hidden against his chest, in an attitude which conveys how great is her loss as she realises and faces up to the knowledge that through her actions, recounted across the two novels, she has lost the man whom she has loved throughout. He too looks like a man who has endured. The gloom of the woodland setting reflects the pain they both feel.